Dear Friends,

Dispatches from Bohemian Splendor is a growing newsletter. Becoming a subscriber is an act of supporting the work of a lifelong, dedicated human artist. Please consider subscribing or becoming a paid member. If you read my works, know that I would love to hear from you and am very grateful for any support that you may be able to lend.

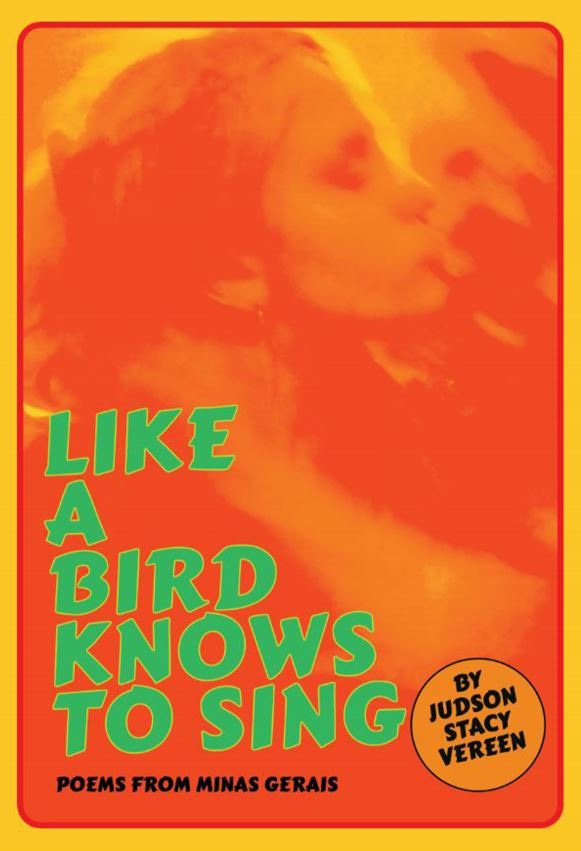

Note: As of June 2025, annual paid subscribers will receive a complimentary PDF of my latest collection of poetry, Like A Bird Knows To Sing.

It is a meaningless Thursday; of course, it is. Lovers have no use for calendars, wristwatches, the factual nature of time—the days of the week, and so on. It is morning, too early. In the taxi, I am still half-drunk, half-asleep. The road dissolves to black at a stop sign, reappears in full color upon acceleration. By my side, you are sitting as attentive as a wartime nurse. We hold hands throughout the drive, and the cab driver won’t shut up. Foz do Iguaçu is misty, miasmic, greyed, grainy—as if everything were being viewed through an old television. In the hotel room, there was an argument of some kind. Can’t remember now what it was about. After a silent breakfast, I realize what a shame it is to ever argue at all, especially on the day of our union.

Marriage. Just outside the state of Paraná, we pierce the border of Brazil. Paraguay will give us a chance. We have all the papers, signed and dated. Every form of identification that one could provide, we have in our possession! We can confirm, affirm, guarantee—can even pay a little money! And how wonderful it will all be! You, a Brazilian by birth, I, just an American. Not even a good American, either. But we have trekked through the gut of Brazil by bus, stifled our vomit in the iron thick air of it, eaten out of bags from gas stations with drooping eyes and hot breath, fumbled for comfort in the dark shuttle as it jets out into the Brazilian black night of nowhere and held our breath from dank flatulence, hiccupping children, snoring laborers, coughing grandmothers, sneezing barefoot drifters, and delirious ass-scratching nobodies. At each stop, a revolving set of faces swirl in a mosaic of one long-fangled expression. Yes, we have travelled. For days on end, it seems. The necessity of it: The Bureaucracy of Love. Paraguay was to make for a quick turnaround; for some reason, to marry there is easy. Anyways, we are convinced I must leave the country and re-enter as a mere formality, or else, the officials of Brazil may ask me to leave for good. Ciudad del Este. In the afternoon heat and hungover, I fall to one knee outside the pitiful city office. You smirk, as if to say “get up, fool—I had said yes the day we met!”. Do you remember their names? Our witnesses? One pulled off the street at random; the other, a jolly woman who owned the café next door. She said she had signed for hundreds of couples…

On the side of the road, there at the office, The Documents And Signatures are now in order. One day for processing by an officiator. We return back to Paraguay in twenty-four hours. So far, so good. Back through the borderline with the military police inspecting endless cars, back over the bridge full of debris and the street sellers hocking corn, dish rags, and peanuts, back inside Brazil, and now inside our hotel room, we are lost lovers in your own birthplace, but husband and wife no further away than the length of a pitiful bridge. Within each of our moving shadows inside the room, we are rediscovered. We eat kibe and falafel and drink beers in bed. We then tumble in the sheets, one of the best yet. After wiping you down, I smoke by the window. The television is blaring colorfully, but is silent. Underneath us, a glimmering swimming pool sits as still as a photograph. Gone are the United States with its endless complications, gone is São Paulo and its streets teeming with throngs of anonymous dolts. We are not there, but here! We have only this room and each other, and everything else in this disease-ridden world can pass by as if being carried out to sea by the pull of the moon.

The next morning, back across the bridge with the street sellers, and through the borderline with the police, and into the officiating building on a dusty little road, we have hit a snag. The official whose signature our marriage requires is in the office today, but is busy. Too busy, in fact. I hear no familiar words in the exchange with the secretary, but they must listen! The hiccupping babies, the dank flatulence—what is this too busy nonsense, get out here and sign the damn paper!

But I speak neither Portuguese nor Spanish. Like I said, not even a good American. We must stay throughout the weekend until Monday for the final paper, we must! Brazil will never recognize our union without it. But we have run out of money. However, we are married. Married in a country of no return. Married in a country whose history is measured in hours. Upon entering Brazil, our certificate is rendered useless; unrecognized by any official perspective. Trekking back through the guts of the country by bus, we are bleary-eyed and starving. Holding hands, we sleep in the vibrations of the moving shuttle. Vibrations of a journey which once had some faint resemblance of utility, but now, in the failure of our first attempt at marriage, have been rendered quite useless.

. . .

In São Lourenço, now, everything is fully domesticated. Our little yellow house is nestled neatly among the cobblestone lanes and broken hills of the Minas Gerais countryside. Laundry hangs on the back landing, among the grandiosity of mountains and the agoraphobic landscape of endless green. I type poetry in the shade. I raise my head and there you appear. Darting across the house in white lace, you wave to me as though from a moving automobile. Marriage. Eva is in the front yard, chewing her toy, bursting through the yard in intense bolts for reasons only she could possibly discern. In those early days, remember going at it in the yard, hoping dear lord the neighbors didn’t see or hear us?! At this point, I wish they had, those prudes!

In the evening, everything got silent, save the dogs. In the yellow house, I felt like my father. I dressed in country denim, flannel, work boots. My days were filled with endless, joyful minutiae. Replacing the shower head, pulling up weeds, tending the garden, rescuing laundry that has flown off its hangers and went strewn across the yard. I moved lumber from one pile to another, invented things to fix, improve. After dinner, one last beer, the last glass of wine. The night’s last cigarette. At dark, the country house glowed with candlelight. In bed, we swim like newlyweds. You wear white satin lingerie and I wear the grin of a younger man. On most nights, wine and cachaça are enough to stave off the boredom. But wasn’t the countryside the dream we sought after? Had we not fought for it? Had we not tried damn hard to secure it? Had we not preached and sermonized the virtues of leaving—those people, those places, all behind us? Had we not stood in that dank office building with your mother and father and finally, were married, and ran back away as soon as we could?