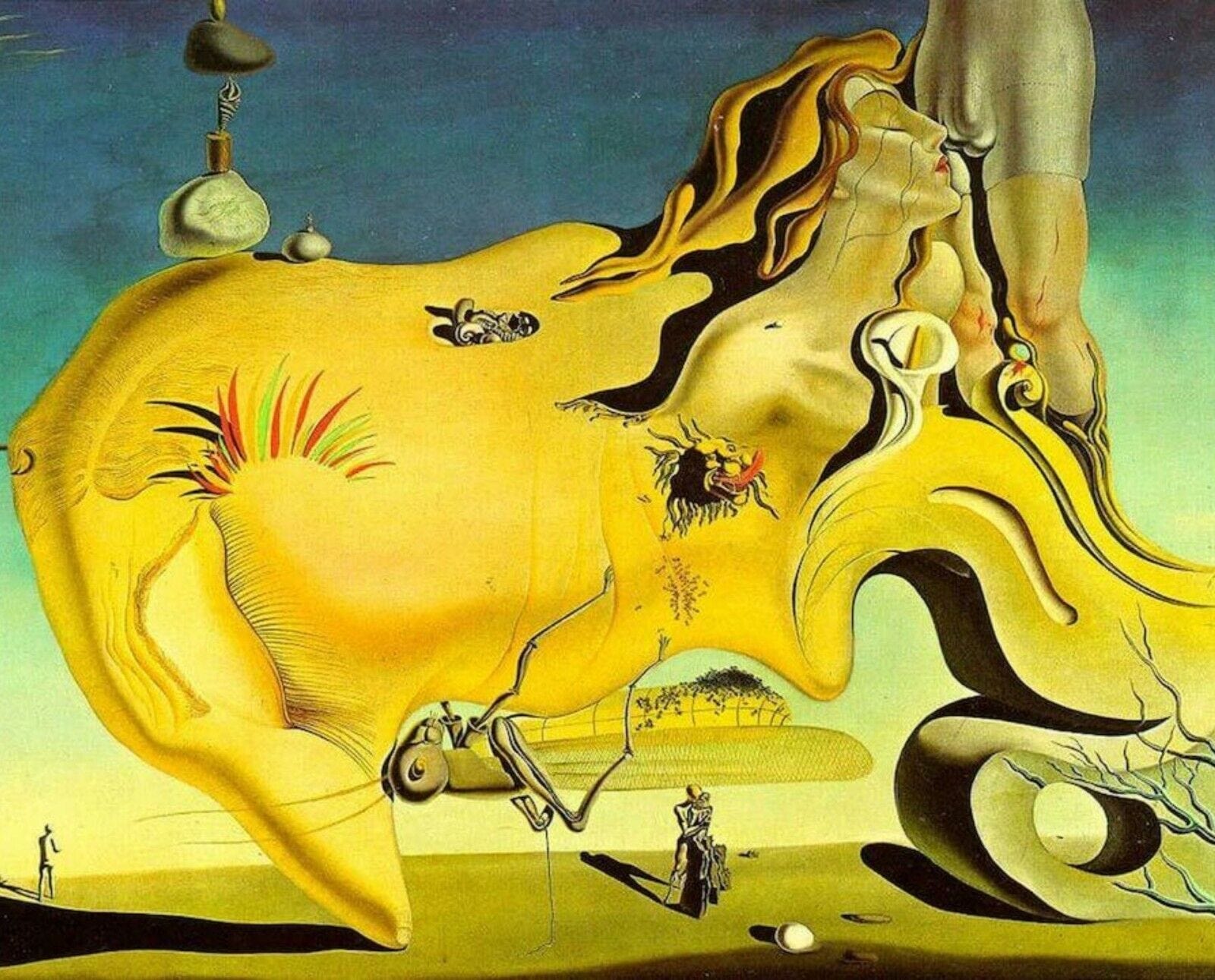

In the desert, wide, vacuous, ochre, cerulean blues fade to a pale yellow. Miniaturized by a vision, two lovers, both donning the color grey as their naked forms, embrace heartily. Their shadow makes no distinction between their shapes and is so long, it reaches the edge of the horizon. As though they had gazed upon Medusa, they’ve turned to stone. Sculpted, eternally still, their embrace, all it contains, all it ever will, dominates the picture plane as a visual feast of uninhibited delights. It is a wild, blossoming image. One which holds the keys to the mysteries of seduction and erotica.

The prosperous grasshopper feeds on the underbelly, which doubles as a man planting himself into the ground. The sticky limbs of the grasshopper clutch the form effortlessly. Inexplicably, he has been culled two of his legs. His oblong body resembles that of buttered corn in a trough. A colony of Carpenter Ants feed on his body. Packed densely, they produce their own form; a cluster of limitless, mysterious movements. The anxiety of sex, the phobia of the infinitesimal. Another colony above, reddish and golden are drawn into a shallow fold of skin. If we are to consider form, which is man and woman, worm and sculpture, we should be lost. It is not to be “considered”, but only taken as fact. The form is generous enough; what more should we require? So generous, it gives birth to another beast: an anthropomorphic lion, who is responding to the scene as though witnessing something delicious. His long tongue laps at the setting. He is wild, lascivious, drooling. He is making his exit from the guts of the figure. Bursting out by the tempting voyeurism of all things seductive. He is small, but grotesque.

On the back of the form, two rocks, extracted from the mountains and never to return are balanced in perfected unison. Upon them, seashells, one resembling the Auger type, perhaps from the Balearic Sea, stand to defy gravity. In a small opening, another cluster of sea shells are burgeoning through skin; their salty conch lives, endless, are corroded, but nevertheless refreshing to the epidermis. Thoughtfully placed in an abandoned, empty location of the form, the shells produce a trypophobia-like quality.

In the downward face of the man, what is the hide of the woman form, is also the top of the man’s head. His golden hair is combed diligently, respectfully. The lashes of his long eyes are closed particularly peacefully. He could be in a deep slumber. He could be dead. Whatever the case, I believe his mind is racing. Yes, even in death it is saturated with mythological beings, religious texts, orgies of the nobility, grand ballrooms of the aristocracy. At the top of his head, he has been hooked as though he were a fish. On the hook, a form resembling a slice of flesh dangles unaffectionately, apathetically.

Now, to the scene. Our eyes have avoided it thus yet, if we have had any shame. The woman and her faceless lover. Gala, the lover of Dali, is caught in a momentary, erotic daydream. Her Clavicle takes on the entire burden of the picture. The smoldering sex of a woman is only complete when gazing upon the collar bone. Without it, the entire form in this picture would collapse. Resting on her shoulder is a single pearl. Planted between her breasts is the blossoming Calla Lily. With it, we are given a nod toward fertility, life, reproduction, but also, death. Directly below, in the closest area of the picture plane lies a solitary egg. There will be, among all that is active and lively, blossoming and evolving, the birth of an unknown bird. The egg does not merit our anticipation, however. The scene is too chaotic, to lively to think beyond the very moment it depicts.

Back to Gala, with her red lips, her carved jaw and clavicle, her umber-golden hair, flowing but heavy, shadowed, shiny. Her eyes, like the form that she grows out of, are also closed. However, they are not closed in a slumber, and certainly not in death or decay. She is transfixed, eroticized in a singly long inhalation of sexual desire. From Kazan to Switzerland, to Costa Brava, her tuberculosis veins rise to the surface of her skin–flush in arousal. In front, a male form rises from the carving of a sculpture. If she is said to have sickly veins, the form at the lower right, too, is bearing a similar sickness. As the form rises, it gives birth to the planted man, recently undressed. Though not aroused, his groin emanates a grotesque but intoxicating effervescence. It is a perfume of life-affirming substances. The perspiration of the groin, damp, moist. Semen, which yearns to be extracted by her mouth, and the faint redolence of urine. An aroma that is at once putrid in large quantity, but enticing when mild.

The faceless man is sturdy, but bleeding. His voyage did not leave him unscathed. Perhaps this will result in a greater sense of gratitude if fellatio is to be performed. But his arrival is frustrating; among his bloody legs, many unwanted guests and intruders, there are no hands. Like dreams of wet socks that will not adhere to feet, or the doorknob that won’t turn, or the lover in the street who cannot hear your call, we are left, right at the very crucial moment, without agency. The act cannot be executed. As though the central figures in stone have spent an entire lifespan, perhaps eternity, waiting for agency, waiting for the possibility of the erotic to take place. So long, that seashells have formed organically, that flowers have blossomed from skin. Where monsters have come to be voyeurs, where ants and grasshoppers have come to feed. Where a single character, a man, has come as a witness, realized its impossibility, and has started walking through the vacuous abyss alone, stultified, as though he had witnessed an image as toxic as chloroform.

JSV

2024

If becoming a monthly paid subscriber is not possible at the moment, but you would still like to support my writing, you may visit my Patreon page HERE to support Dispatches from Bohemian Splendor. I aim to keep the page as free as possible, even small amounts help keep my work afloat.

Something always fascinating to me in Dali's paintings of this period are his little figures walking away in the distance with seemingly no connection to the rest of the image. There is also a good one in "Premonitions of Civil War."

10 words

Beautifuly perverse dreamscape turning adolescence from black/white to color